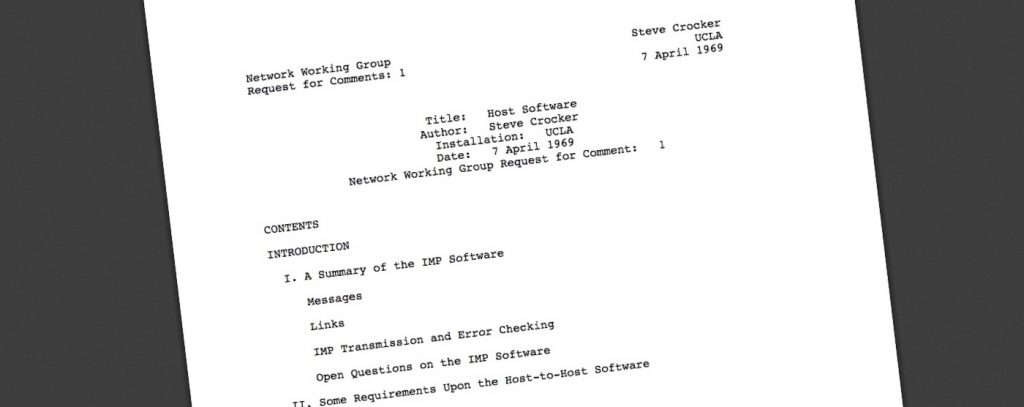

50 years ago today, on 7 April 1969, the very first “Request for Comments” (RFC) document was published. Titled simply “Host Software”, RFC 1 was written by Steve Crocker to document how packets would be sent from computer to computer in what was then the very early ARPANET. [1]

Steve and the other early authors were just circulating ideas and trying to figure out how to connect the different devices and systems of the early networks that would evolve into the massive network of networks we now call the Internet. They were not trying to create formal standards – they were just writing specifications that would help them be able to connect their computers. Little did they know then that the system they developed would come to later define the standards used to build the Internet.

Today there are over 8,500 RFCs whose publication is managed through a formal process by the RFC Editor team. The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is responsible for the vast majority (but not all) of the RFCs – and there is strong process through which documents move within the IETF from ideas (“Internet-Drafts” or “I-Ds”) into published standards or informational documents[2].

50 years ago, one of the fundamental differences of the RFC series from other standards at the time was that:

- anyone could write an RFC for free.

- anyone could read the RFCs for free. They were open to all to read, without any fee or membership

As Steve Crocker notes in his recollections, this enabled the RFC documents to be widely distributed around the world, and studied by students, developers, vendors and other professionals. This allowed people to learn how the ARPANET, and later the Internet, worked – and to build on that to create new and amazing services, systems and software

This openness remains true today. While the process of publishing a RFC is more rigorous, anyone can start the process. You are not required to be a member (or pay for a membership) to contribute to or approve standards. And anyone, anywhere, can read all of the RFCs for free. You do not have to pay to download the RFCs, nor do you have to be a member of any organization.

More than anything, this open model of how to work together to create voluntary open standards is perhaps the greatest accomplishment of the RFC process. The Internet model of networking has thrived because it is built upon these open standards.

Standards may come and go over time, but the open way of working persists.

While we may no longer use NCP or some of the other protocols defined in the early RFCs, we are defining new protocols in new RFCs. The next 1,000s RFCs will define many aspects of the Internet of tomorrow.[3]

We may not know exactly how that future Internet will work, but it’s a pretty good guess that it will be defined in part through RFCs.

- See also: Fifty Years of RFCs – reflections from current RFC Editor Heather Flanagan.

[1] See our History of the Internet page for more background.

[2] For more explanation of the different types of RFCs, see “How to Read a RFC“.

[3] As noted in our 2019 Global Internet Report section on “Takeaways and Observations”, we are concerned that an increasing number of new services and applications on the Internet are relying on application programming interfaces (APIs) controlled by the application or platform owner rather than on open standards defined by the larger Internet community.

The post Celebrating 50 Years of the RFCs That Define How the Internet Works appeared first on Internet Society.